The term “f-stop” plays a crucial role in photography, particularly when discussing aperture and light control.

The “f” in f-stop comes from the word “focal” and represents the ratio of the lens’s focal length to the diameter of the aperture. This concept is essential for understanding how much light enters the camera, affecting exposure and depth of field.

In photography, the aperture is the opening in the camera lens that allows light to pass through. Adjusting the f-stop changes the size of this opening, directly influencing the amount of light that hits the camera sensor.

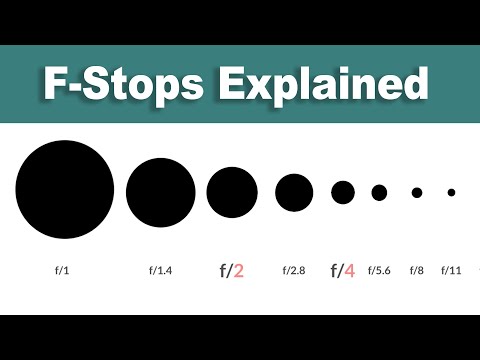

A lower f-stop number indicates a larger aperture, letting in more light, while a higher number signifies a smaller opening, which reduces light.

Understanding why it is called an f-stop opens the door to mastering photographic techniques. By manipulating aperture settings, photographers can create images with different lighting effects and focus qualities, enhancing their creative expression.

The Science Behind F-Stop Numbers

F-stop numbers are crucial in photography, linking aperture size to the amount of light that reaches the camera’s sensor. Understanding these principles helps photographers manage exposure effectively.

Understanding Aperture Size and Light Transmission

Aperture refers to the opening in a camera lens that allows light to enter. This opening’s size directly impacts the amount of light that reaches the sensor.

A larger aperture means more light can pass through. For example, an aperture size of f/2.8 allows more light in than an f/16 setting. This significant difference can affect a photograph’s exposure and depth of field.

Key Points:

- The larger the aperture (smaller f-stop number), the more light transmitted.

- Aperture affects the focus area, influencing sharpness.

Each f-stop represents a specific light transmission amount. A change in f-stop by one full number (like from f/4 to f/2.8) doubles the light entering the lens.

F-Number and F-Stop Relationship

The f-number, or f-stop, is a ratio that defines the lens’s aperture size relative to its focal length. The formula is:

[

\text{f-stop} = \frac{\text{focal length}}{\text{diameter of the aperture}}

]

For instance, with a 50mm lens at f/4, the diameter of the opening is 12.5mm.

This relationship is essential for understanding exposure. Each f-stop change either doubles or halves the light entering the camera. For example:

- f/2.8 → doubles light compared to f/4.

- f/8 → halves light compared to f/5.6.

Photographers need to grasp these concepts to control exposure and achieve the desired effect in their images. Understanding the links between f-stop, aperture, and light is foundational for mastering photography.

How F-Stops Affect Photography

F-stops play a crucial role in photography, influencing both exposure and depth of field. Understanding how to manipulate f-stops helps photographers achieve desired artistic effects in their images.

Depth of Field and F-Stop Correlation

Depth of field refers to the range of distance that appears sharp in a photograph. It is significantly affected by the f-stop. A lower f-stop number, like f/2.8, results in a wider aperture. This allows more light to enter the camera, creating a shallow depth of field. This effect is ideal for portraits, where isolating the subject from the background is desired.

Conversely, a higher f-stop, such as f/16, produces a smaller aperture. This lets in less light and increases the depth of field. In landscape photography, using a higher f-stop helps keep both the foreground and background in focus. Adjustments to the f-stop can significantly alter the creative impact of an image.

The Exposure Triangle: ISO, Shutter Speed, and Aperture

The exposure triangle consists of three key elements: ISO, shutter speed, and aperture. Each component influences how much light reaches the camera sensor. The f-stop, or aperture size, is crucial in this triangle.

When a photographer selects a low f-stop, more light enters the camera. This allows for faster shutter speeds, which can reduce motion blur in dynamic scenes.

Conversely, when using a high f-stop, the photographer might need to increase the ISO or slow down the shutter speed to compensate for the reduced light. Balancing these three settings enables control over exposure in various lighting conditions.

Field Examples: Landscape vs. Portrait Photography

In photography, different settings suit various types of images. For landscape photography, a high f-stop like f/11 or f/16 is beneficial. It keeps more elements in focus, resulting in detailed and immersive scenes. Landscapes often require clarity from foreground to background, and higher f-stops help achieve this.

In contrast, portrait photography typically utilizes lower f-stops, around f/2.8 to f/4. This creates a soft background blur, enhancing the subject’s features and drawing attention to them. By choosing the appropriate f-stop, photographers can tailor their images to convey specific emotions and details, ensuring each shot meets their artistic vision.

The F-Stop Scale and Practical Usage

Understanding the F-stop scale is crucial for mastering photography. This knowledge helps photographers choose the right settings to manage light and enhance image quality in various situations.

Reading the F-Stop Scale on Lenses

The F-stop scale is marked on camera lenses, typically using numbers like f/1.4, f/2, f/2.8, f/4, and so on up to f/22. Each number represents the aperture size, which is the opening through which light enters the camera.

A lower number, such as f/1.4, indicates a larger aperture, allowing more light. Conversely, a higher number, like f/16, represents a smaller opening, letting in less light.

This scale is not linear; each full stop change either doubles or halves the amount of light reaching the sensor.

To read the scale, photographers can look for notches or markings on the lens barrel. Knowing where a lens sits on this scale helps them adjust settings quickly based on lighting conditions.

Selecting the Right F-Stop for Your Scene

Choosing the right F-stop depends on the desired depth of field and light availability. For bright outdoor settings, using a higher F-stop like f/11 or f/16 can create a sharp image with a wide depth of field, keeping most of the scene in focus.

In contrast, lower F-stops, such as f/2.8 or f/4, are suitable for portraits. They create a blurred background, making the subject stand out.

In low light situations, opting for f/1.4 or f/2 can help capture more light, reducing the need for a flash while keeping shutter speed fast enough to avoid motion blur.

Photographers often use aperture-priority mode to let the camera automatically adjust shutter speed while they select the desired F-stop, making it easier to achieve optimal exposure.

Advanced Techniques: Low-light and Motion Blurring

In low-light conditions, photographers can exploit larger apertures like f/1.4 or f/2 to gather more light. This approach is beneficial for night photography or indoor events where lighting is limited.

Additionally, when trying to capture motion, a larger aperture allows for faster shutter speeds. This combination results in sharp images of moving subjects while minimizing motion blur.

For instance, using f/2.8 in a sports setting can freeze the action, keeping the subject crisp.

On the other hand, smaller apertures like f/11 or f/16 create greater depth of field, which can enhance background details. This technique is vital when photographing landscapes where sharpness across the entire frame is desired.

Understanding Lens Specifications and F-Stop

F-stop refers to the aperture setting of a lens, which influences exposure and depth of field in photography. Knowing how to interpret lens specifications is essential for making informed choices about gear. This section explores the maximum and minimum aperture ratings, how lens focal length affects aperture, and tips for selecting the right lens.

Interpreting Maximum and Minimum Aperture Ratings

A lens’s maximum aperture determines how much light it can let in. Common ratings are f/1.8, f/2.8, or f/4. A wider aperture, like f/1.8, allows more light, making it suitable for low-light conditions.

Conversely, a minimum aperture, such as f/16, restricts light, which can enhance depth of field, beneficial for landscape photography.

The f-stop number reflects the size of the lens’s entrance pupil. Higher f-stop numbers mean a smaller aperture. This affects exposure and the amount of background blur, or bokeh, photographers need. Understanding these ratings helps in making choices that cater to specific photography needs.

Impact of Lens Focal Length on Aperture and Depth of Field

Lens focal length plays a significant role in how an aperture operates. A 50mm lens often provides a different depth of field than a 100mm lens at the same f-stop number.

Longer focal lengths compress images and decrease the depth of field. This can create a softer background, ideal for portraits.

Shorter lenses, like a 24mm, typically yield a greater depth of field at similar f-stop settings. This means more of the scene will be in focus, suitable for wide-angle shots like landscapes. Understanding how focal length influences depth of field helps photographers choose the right lens for their artistic vision.

Choosing the Right Lens for Desired F-Stops

Selecting a lens involves considering the desired f-stops for particular photography styles.

For example, a fast lens with a maximum aperture of f/1.4 is perfect for shooting in dim lighting or achieving strong background blur.

When shooting landscapes, a lens with a minimum aperture of f/16 or f/22 is ideal for greater depth of field.

Photographers should also consider the number of aperture blades, as more blades can produce a smoother bokeh effect.

Evaluating these factors ensures the lens meets specific artistic and technical requirements.