An aperture is a crucial component in optics, playing a vital role in how light interacts with lenses and optical systems.

An aperture is essentially an opening that controls the amount of light that passes through a lens, directly affecting image quality and brightness.

This concept is essential in photography, telescopes, and various scientific instruments where precision in light manipulation is needed.

By adjusting the size of the aperture, one can influence not only the exposure of an image but also the depth of field, which determines how much of the scene appears in focus.

This ability to manage light makes the aperture a powerful tool for photographers and researchers alike, allowing them to enhance their images and observations through careful control of light.

Understanding the function of an aperture can unlock new possibilities in both art and science. It bridges the gap between technical precision and creative expression, making it an intriguing topic for anyone interested in the workings of optics and the impact of light on imaging.

Fundamentals of Aperture

Aperture plays a key role in how optical systems manage light. Understanding its definition, its impact on light transmission, and the importance of size can enhance the clarity and depth of images in various lenses.

Definition and Role in Optics

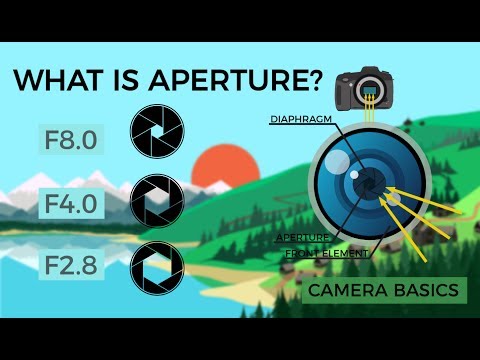

An aperture is an opening that controls the amount of light entering an optical system. It is a crucial element in cameras, telescopes, and other optical devices. The design of the aperture influences the brightness and sharpness of an image.

In simple terms, larger apertures allow more light in, which can brighten the image. This is particularly important in low-light conditions.

The aperture is often adjustable, enabling photographers to experiment with depth of field and focus. A smaller aperture creates a greater depth of field, keeping more of the scene in focus. This effect is particularly useful in landscape photography.

Aperture and Light Transmission

Light transmission through an aperture is vital for image quality. The numerical aperture (NA) helps measure how much light the lens can gather. It is a dimensionless number that indicates the light-gathering ability of an optical system.

A higher numerical aperture means more light and better imaging performance.

In optics, brightness is often influenced by the aperture size. A larger aperture enhances brightness, making it easier to capture details in dim environments.

The relationship between the aperture and light is key to understanding how images are formed in both binoculars and monoculars. Proper aperture settings ensure that the right amount of light contributes to sharp, clear images.

Aperture Size and F-Number

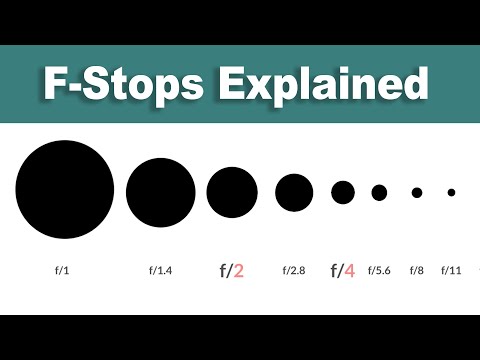

The size of an aperture is commonly expressed using the f-number or f-stop. This value is calculated by dividing the focal length of the lens by the diameter of the aperture.

For example, an f-number of f/2.8 indicates a larger aperture than f/8. A smaller f-number means a wider aperture, allowing more light to enter.

Photographers often choose their f-number based on the desired effects. A lower f-number creates a shallow depth of field, which can blur the background and focus attention on the subject.

Conversely, a higher f-number increases depth of field, ensuring that more elements are in focus. Understanding the interplay of aperture size and f-number is essential for achieving the desired artistic effect in photography.

Calculating and Using Aperture

Aperture plays a crucial role in optics, particularly in photography and microscopy. Understanding how to calculate and use aperture helps in achieving the desired image quality. Key aspects include f-stops, their impact on depth of field, and variations in different optical instruments.

Understanding F-Stops

F-stops measure the size of the aperture opening in a lens. The f-stop number is calculated as the lens focal length divided by the diameter of the aperture.

For example, a lens with a focal length of 50mm and an aperture diameter of 25mm has an f-stop of f/2. This means a larger aperture allows more light, creating a shallow depth of field and producing soft backgrounds.

Conversely, smaller f-stop numbers like f/16 allow less light, resulting in a greater depth of field. This is useful in landscapes where sharpness is required from foreground to background.

Mastering f-stops enables photographers to control exposure and achieve specific artistic effects.

Impact on Image Sharpness and Quality

Aperture significantly affects image sharpness and overall quality. At wide apertures like f/2.8, images appear brighter but can suffer from reduced sharpness at the edges due to optical aberrations. This is particularly true in lenses of lower quality.

As the aperture narrows to values like f/8 or f/11, images generally become sharper. This is often referred to as the sweet spot of a lens.

It is during this range that the resolution is optimized, enhancing the detail captured by camera sensors. Understanding this relationship is vital for photographers when choosing settings for different scenarios.

Aperture in Different Optical Instruments

In various optical instruments, such as cameras and telescopes, aperture plays a distinct role. In photography, a large aperture (like f/2.8) allows for faster shutter speeds, essential for capturing fast-moving subjects.

In telescopes, the aperture determines the amount of light gathered and thus the clarity of distant objects. A larger aperture will provide better visibility of faint celestial bodies.

For instance, advanced telescopes can greatly benefit from larger apertures to enhance visibility of celestial phenomena. For more insights on telescopes, refer to resources on telescopes.

Advanced Aperture Concepts

This section explores intricate aspects of apertures in optics, detailing their role in complex systems and how they relate to image quality through diffraction limits and optical aberrations.

Aperture in Complex Optical Systems

In complex optical systems, apertures play crucial roles in determining light behavior. They are usually defined by a diaphragm that controls the amount of light entering the system.

The size of the aperture influences the depth of field, which refers to the range of distance that appears sharp in an image.

Each optical system has an aperture stop that affects the exit pupil and field of view. The entrance pupil is effectively the image of the aperture as seen from the front.

Together, they dictate how light rays converge, impacting image brightness and clarity.

Adjusting the aperture size can change the cone angle of incoming light, altering the magnification and overall imaging performance. For example, a smaller aperture increases depth of field but may reduce brightness.

Diffraction Limit and Optical Aberrations

The diffraction limit defines the smallest detail that can be resolved by an optical system. It arises due to the wave nature of light and is influenced by the aperture diameter.

A larger aperture can enable better resolution, but it also can lead to optical aberrations, which are imperfections that distort the image.

Common types of aberrations include spherical and chromatic aberrations. Spherical aberration occurs when light rays strike the lens at different points, causing blurriness. Refraction at the aperture can also affect how light bends, adding to potential distortions.

Managing these factors is essential for high-quality imaging, especially in precision devices like microscopes. Understanding these advanced concepts allows for enhanced control over imaging systems and improved overall performance.